🇮🇹 MICOL & LUCIA

Verona, January 2022

Connecting

Zoom Call 752 5781 4100, Micol sits at the table with her grandmother Lucia in the living room in Verona, in north-eastern Italy. Micol wears a mask, Lucia doesn’t. The (analogue) room is dark, with only one light illuminating the faces of the two women. I'm sitting at the airport in Lisbon, which is very crowded as everyone is flying back from family visits and holidays.

First try for the call... The internet doesn't work, and my headphones don't shield the noise of the airport hall sufficiently. New attempt, new headphones and a new internet connection... Finally, we hear and see each other. Corona has once again decided everything differently, especially this Christmas and New Year's Eve 2021/2022. Hardly anyone has gotten around to either being infected or at least being a contact person during this time. Every other Instagram Story is a person announcing their quarantine with a glass of wine, a full bath or delicious food their seclusion. My plans to go to Verona also fell through a few weeks early, due to the famous Omicron. So that's why I'm not sitting with Micol and Lucia together in their living room in Italy but in an airport lounge.

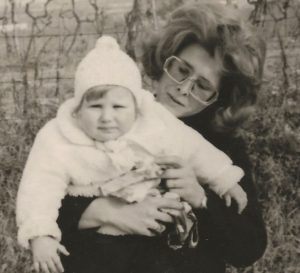

Micol (27) and Lucia (84) were both born in Verona, in 1994 and 1938, respectively. They both studied abroad for a while and they like to go to the Alps in the north of Italy, the Dolomites, when snow has fallen and in the summer. Both did a semester abroad but Lucia and Micol chose two different countries for their stay, so the interview is a mishmash between French, German and Italian. My transcribing programme invents all sorts of German, French and Italian word combinations as I work it out.

I know Micol from Brussels, where she works as a consultant in the field of free trade. What consultant really means in Brussels is a mystery to many. Micol has long brown hair, but during the interview on a Monday morning while still on holiday, she knotted her hair in a bun. Her eyes are an intense brown colour. She is wearing a red plain jumper. During her Bachelor’s degree, she did an Erasmus year in France, in Besançon, a small French town in an industrial region not far from the Peugeot factories. Later, she did her Master's in Paris. She speaks French fluently. If she had French citizenship, she would immediately work for the Quai d'Orsay, the French Foreign Ministry. She is no longer in touch with Italian national politics. Too non-transparent, too many complex procedures and, above all, too little change. Now she is stuck in Brussels for the time being, not her dream city, but after a few months in which Corona doesn't dictate the possibilities for going out, Micol is settling in quite well. The beginning of Corona, however, remains a significant moment in her life. Suddenly everything was different, it was all about finding a job quickly. No time to look around again, too dangerous in a time of crisis in the job market. Like so many, she finished her Master's online and the only consolation to replace the graduation was a goodie cup from Science-Po Paris a few months later.

With a somewhat bitter tone, she tells of her arrival in Brussels. For her work, she was actually supposed to meet a lot of people and have direct exchanges, something she had been looking forward to. But now, after several months, the meetings are still taking place online and there is no prospect of canapés, wine and analogue conversations with partners and clients. Micol sums up her 27th year with"pas génial " (Not great.. That sums it up well: her awareness that she was lucky to find this job, but still mourns lost opportunities. She knows her world to be completely different from that of her grandmother at the same age. Micol says that she inherited a world for which she was not prepared. Yet she is divided between the advantages she has as a young woman compared to her grandmother and the disillusions especially in her country, which is still struggling with the aftermath of the 2008 crisis. Corona has had the greatest impact on her adult life. Micol also remembers the change of currency in Italy, which went badly at first, but later had rather positive consequences for her. Overall, in the long run, the EU has shaped her life and allowed her to live in two countries for a longer period of time.

I only got to know Lucia through the zoom screen. She could be very tall and not shrunk in age, I can't see that exactly. What is certain is that Lucia has full and white hair, cut short. Round brown eyes looking at me from behind her large red glasses. Lucia has prepared herself for the conversation and looks at her notes, which she has written in German! Lucia chose Germany in the 1960s and went to Tübingen to study for a few months. From Verona, the German-speaking South Tyrol is only a few kilometres away. Switzerland, Austria and Germany are also around the corner.. In her childhood around the corner were mainly the Nazis. Lucia doesn't have many memories of wartime. She remembers that they moved from the small town Rovigo, where her father worked, to a village because bombings had made life difficult. They spent the last 6 months of the war in a farmhouse with 19 other families, only 5 kilometres from the Gotenstellung. The Gotenstellung, also called the Green Line, is the demarcation line that stretched from Massa-Carrara to Pesaro. In 1944, German troops were positioned to the north of that line and the American and British Allies to the south. The fiercest fighting took place in the summer and autumn of 1944. When the war was over, Lucia was only 7 "But you had nightmares about the war until you were 30 years old." Micol remembers from stories. Lucia makes a dismissive hand gesture.

At this point, I repeat that if there are questions that she would rather not talk about because they might be a trigger, she needs only to say so and we skip the topic. But Lucia responds in German with „I am still living, so I can tell my stories."

20 years later, at 27, it was a "good time for me. Almost everything was finally over, there was work and you could eat well" . That year she had her first child, Micol's mother, and teaches at a school from which she takes three months off to give birth. After a while, it gets a bit tiring for the 84-year-old to keep up the conversation in German, sometimes she turns to Micol and both women exchange a few words in Italian, which Micol translates to me in French or English.

Immersion

In den 1960er-Jahren hatte es eine ganz andere Bedeutung, für eine Frau allein ins Ausland zu reisen – besonders im Vergleich zu der Zeit, als Micol nach Paris ging. Deutsch hatte Lucia bereits vier Jahre lang an der Universität studiert, bevor ihr Vater ihr erlaubte, einen Auslandsaufenthalt in Deutschland zu machen. Sie hatte Glück, dass ihre Eltern sie überhaupt gehen ließen. Eine große Rolle hat dabei gespielt, dass ihr der sisters' order of Verona, which her father knew, was able to arrange the contact to Germany. There was still a place available for Lucia in the student house in Tübingen for the summer. Lucia's parents accompanied her to Swabia.Es war wichtig für meine Eltern zu sehen, wo ich genau hingingIn July, when Lucia arrived, the students were still in the house until the holidays, so she spent two weeks in a retirement home until her room became available. Lucia was a bit desperate in the old people's home, all the older ladies spoke a strange German that she couldn't understand. They chatted in Swabian for a fortnight. geschwätzt. Later in the student house, Lucia felt at home and made friends who came from Halle (Saale) and were very patient in practicing German with her. The following year, Lucia went back to Germany. Actually, Lucia would have liked to stay in Germany: ""In my head I am German". But between her stays, she met her future husband in Italy and went back to get married.

She has remained connected to Germany for a long time. She accompanied the exchanges between Munich and Verona, took care of the translation and received many pupils and teachers in Verona. In the last few years that she has been working, she has noticed that the pupils have become more interested in the language, culture and encounters as a whole. She does not know if the partnership will continue today. Nevertheless, she has tried to visit her friends in Germany once a year for a long time to keep up with her German. Lucia would have liked to live in Micol’s time so that she, too, could have had her "Erasmus experience".

„Lucia has also been able to live abroad,", I ask myself. "What is the difference between her experience and yours Micol?", am I asking out loud . "The normalisation and the availability," Micol answers me. Today, it has become almost compulsory to get an international education, it is expected.

Still, I remember a discussion we had with Micol a few weeks earlier, where we both complained about the difficulties in preparing for and following up on our Erasmus. The uncertainty about whether the universities would recognise our achievements, the scholarship that was barely enough to live on, and the chaos when Micol in France didn't know what day the university started. And above all, the hunt for signatures at different places. But even though her Erasmus experience cost her a lot of nerves and she was lucky enough to write a French exam in"Droit d’affaires International" without a dictionary. She likes to talk about that time. At that moment, the grandfather walks past behind the camera, looks at us with a quick glance, and then continues on his way.

We continue our conversation. How do Lucia and Micol look to the future? For Lucia, despite her already long life, there is no event worth mentioning from the past that keeps her very busy. She is mainly concerned with the climate crisis. Lucia says that awareness has come so suddenly, although it has been known for decades. I ask them both at the end, do women* have power today? Lucia says: "I want to see the time when women also have power. There were no women in power then, and I am still waiting." In Italy, for example, there are 25 people in the government and 8 of them are women. Micol continues to talk for them both so that her grandmother can rest. Lucia and Micol are of one mind, rather, pessimistic that women can ever get into positions of power without ifs and buts.

We continue our conversation. How do Lucia and Micol look to the future? For Lucia, despite her already long life, there is no event worth mentioning from the past that keeps her very busy. She is mainly concerned with the climate crisis. Lucia says that awareness has come so suddenly, although it has been known for decades. I ask them both at the end, do women* have power today? Lucia says: "I want to see the time when women also have power. There were no women in power then, and I am still waiting." In Italy, for example, there are 25 people in the government and 8 of them are women. Micol continues to talk for them both so that her grandmother can rest. Lucia and Micol are of one mind, rather, pessimistic that women can ever get into positions of power without ifs and buts.

A second time the grandfather walks past the camera, this time he also stops briefly and walks toward the camera, with an interested look on his face. He wants to say hello once. Micol and her grandparents briefly exchange a few sentences in Italian and far from the mike, laugh a little, and then both women turn back to the camera.

Towards the end of the interview, after Lucia has been quiet for a while, she remembers a story she wants to share. When they lived in the stable, 2 German soldiers were found in the food chamber, they had deserted. Lucia’s mother waited a while until she got the courage to get the bread and prepare the food for the children. When they saw her, the German soldiers got up immediately. Later she spoke a little German with the soldiers and even gave them some food. After a short time, the two soldiers had to leave. Lucia says, a little puzzled, "We had badly hidden bicycles, the most valuable thing in this farm and still the soldiers did not take them." Looking back, Lucia is very grateful:"it's lucky that my mother knew German, my mother never let us children feel fear.".“

After about an hour of discussion, Micol looks at her watch, it is lunchtime, and now the table is set. The interview is over with a click. I need a few minutes to get used to the noise of the hall again and to sort out my thoughts. In my mind, I still have the small town of Verona, not far from the Alps, and two women who were born there and yet grew up very differently.